seeking subversion

"You don't get it. It's supposed to subvert your expectations!"

Subverting expectations used to be good. What happened?

When I first started reading books and watching movies, I enjoyed tropes before I knew they were tropes. While I wasn’t aware of them at the time, I loved every predictable arc and going into films with the internal assurance that everything would be okay. Starting out, nothing ever violated my expectations of a happy ending or optimism winning out in the end.

However, when really popular groundbreaking things get constantly referenced and remixed, it makes the original look quaint in comparison (see: “Seinfeld” is Unfunny). Consequently, as I watched more movies, tv shows and videos, I became hyper aware of the cliches and tropes. This continual predictability started to render everything increasingly inert. So I turned to subversion.

Effective subversion became a thrill-seeking activity of mine. Barry on HBO, the early seasons of Game of Thrones, No Country for Old Men, Se7en, and many horror movies did this well. I thought it was poetic when a movie teased you with a happy ending and ripped it away. Bittersweet or sad endings became something that I felt was just “life as it is.” And so I simply accepted it. It felt meritorious.

But subversion became drier the more I sought it too. It felt overly cynical, lacking real narrative purpose and thus, power. The devastation you’re supposed to feel at a subversion is meant to be that which is carefully constructed throughout the whole of the media you’re engaging with. A blindsided subversion feels cheap. Yet, I was starting to see lots of those. Your main character gets away with something morally dubious and then gets run over by a bus. Not very compelling storytelling.

You also never really see subverted expectations as something that results in the “good ending.” An ending or plot decision that violates your expectations in an optimistic way. There is greater demand for the shocker, plot twist endings. I got burnt out on it.

This reminds me of one of Variety’s Actors on Actors videos which features Robert Pattinson and Jennifer Lopez. In it, Pattinson says, “I always say about people doing method acting, you only ever see people doing method when they’re playing an a**hole. You never see someone just being lovely to everyone going, ‘I’m really deep in character’.” Just like method acting, it’s only really the downer “subversions” that ever seem to get made.

Very rarely would I see a subversion that was such that my expectations of pessimism was outstripped by an optimistic ending.

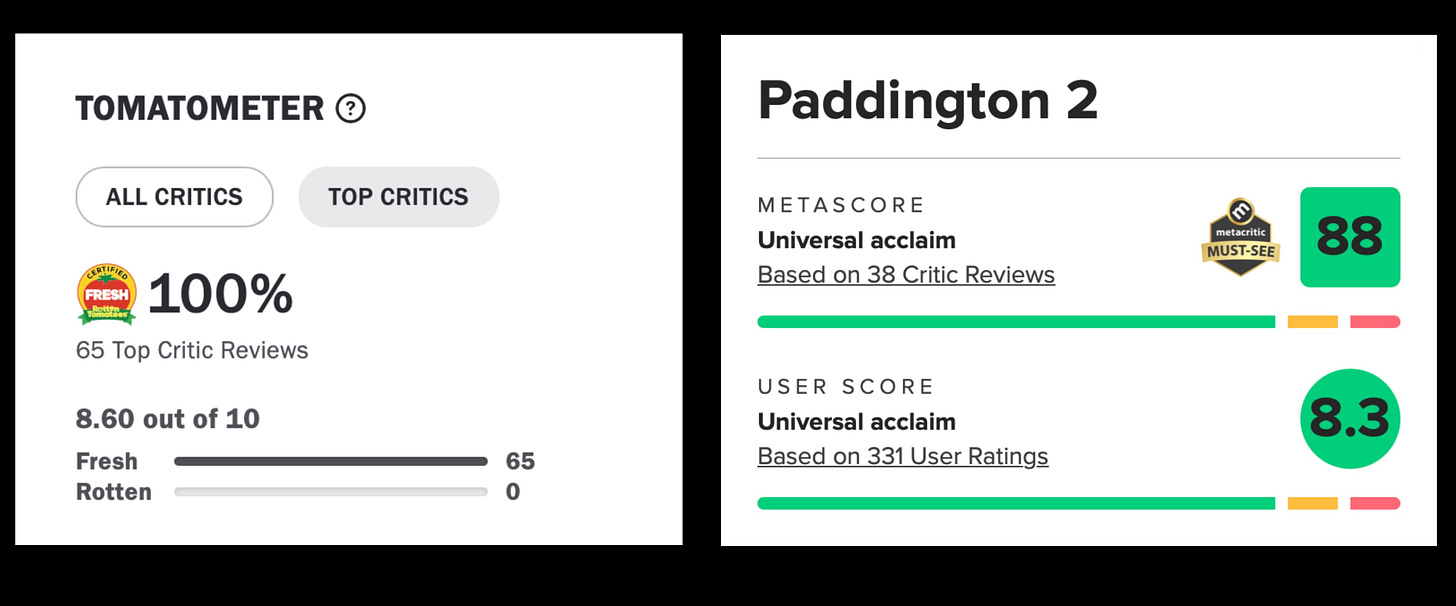

Happy endings can earn critical merit. In defense of this point, I will point to Paddington 1 and 2. They’re earnest films. They’re quite effective because of their willingness to be happy and without reservation. There is no undercutting the good moments with caustic sarcastic humor for the sake of subversion. It is played as it is and it is so refreshing. Some people’s gripes with the Star Wars sequel trilogy and Marvel Cinematic Universe fell along these lines. Sincere moments were frequently undercut by wisecracks making everything feel like it was a parody of itself. It signaled an aloofness from the material.

Paradoxically, burning out on subversion after seeking it for so long had the effect of resetting my brain chemistry. I’d gotten so used to expecting downer endings in things that I was pleasantly surprised whenever my fears were unfounded. I noticed whenever I was watching things, I had unconsciously braced myself, steeling myself in anticipation for my fledgling optimism to be dashed unceremoniously by an all-powerful storyteller. It’s a bit like when you see the side profile shot of someone driving while talking to someone else. You can’t help but feel a tension or unease build up as they take their eyes off the road to talk to the other character. You are curled within yourself expecting an impact either from the side or the front.

For a long time, it felt as if the story tellers I was looking for were ones that always spoke grimly. Their tales were often scalding warnings, paranoia inducing agents designed to seed distrust and undermine my faith in humanity (see: Succession). I realized that what I had deprived myself of were the storytellers that reminded me of my father. He’s the best one I know.

Growing up, he would tell me a combination of children’s stories, more involved plots, and historical things. But these stories were never cheap, they were carefully articulated. They instilled an awe for history in me. An appreciation for bravery, and how things could be. I was fond of the storyteller’s role.

Yet lately, I had an antagonistic relationship with most of the ones that I was coming across. Subverting expectations cheaply can be sniffed out by audiences quickly. While a universal story is generally limited in the level of complexity it can artificially introduce due to losing audiences in the fray, this does not mean audiences are stupid. It would probably take another extensive post and a half to talk about the specific infamous subversions that didn’t sit right with audiences. I will save that for another day.

In time, I found myself valuing execution over “surprise.” Great execution of trope is better than a subpar subversion. In fact, I think it makes the film stronger when I am able to look at a film and be so utterly engrossed by it that I forget that everything is going to be okay. You know when you get on a rollercoaster you’ll be okay, but the architecture of the drops, the twists and turns make for a unique experience that tells your gut and your mind just how thrilling it was.

Scott’s tweet resonated with me. “A good movie does not need to reinvent the wheel, it only needs to roll it well.”

The perfect execution of a trope will always be better than a subpar subversion.

Movies like Casablanca, Titanic, Jurassic Park, Avatar and Top Gun Maverick, understand this. They possess a sincerity that runs through their sinews.

Let’s take Avatar, for example. Blue alien people that love the ecosystem, living in worship and deference to a higher power? Taken at face value, it seems downright goofy! Yet, in the theater, you buy it wholesale. The characters have real heft to them. Decisions have consequences, whether they are good or bad. It’s entirely straightforward storytelling that wears its heart on its sleeve.

These tropes are not cheaply told, which is why they have cultural cachet and/or incredible box office returns. There is no meta-referential humor that points at itself saying “Ha! I know the tropes! I know what you’re thinking!!” to make its audience feel smarter. It simply plays it as it is. It’s not a gimmick, it’s movie magic.

That, to me, is admirable.