immersion induced blindness

How focused do we have to be to become high achieving?

Today, I'm thinking about excellence and in particular, my thoughts turn to a renowned jazz pianist, chess prodigy, and a blockbuster film director. Why? Well, they all share a common perspective to a question many artists have.

"What does it take in order to make great works and achieve excellence in your craft?"

One answer? "Intense focus, deep relaxation."

Now, there is no definitive, prescriptive answer to this question. What follows is not pretending to be. Instead, it's a more descriptive view where I connect examples that share a common theme.

Everything tugs at our sleeves nowadays, begging for attention and a lot of us give it freely without second thought.

When we work on our computers, tap away at keyboards, and scroll social media feeds, we may get so drawn into them that we literally stop breathing. Several people have documented this experience of shallow or paused breathing before, resulting in the term "screen apnea."

The internet is a super stimulus, and many of us don't know how to make it a natural extension of us, rather than restrictive. The abundance of choice paralyzes so much so that now, there's even a shift away from the search bar. Don't know what you want to watch? Don't worry, the algorithms will feed you what you should see. Nothing to worry about there, it's nutritionally complete!

I've heard many stories of people so disproportionately adept in one field yet have little social awareness or charm in navigating other knowledge domains or their public affairs. You'll recognize this by variants of the phrasing: "I don't agree with everything [popular figure] says/believes *but* they're great at what they do." It seems like a point to detract someone's status or qualify your appreciation.

It's devotion that lets them be so great in one respect and underdeveloped in many others. What does it mean to devote yourself to something wholeheartedly, whole-mindedly, whole-bodily? How can you can break through mediocrity and become great? Through intense focus. This singular focus comes at a cost, which I've taken to calling immersion induced blindness. It's the tunnel vision that misses the forest for the trees.

Yet the advantages of such vision may not be ignorable. Simplicity rules. A lot of people seem preoccupied with increasing optionality but more options generally leads to fewer true commitments. There is value to pursuing fewer things, with more focus, that naturally build off each other. I'm personally still experimenting with this. I have a lot of interests, but I only concentrate my efforts at 1-2 at a time because that’s what can get my purest distillation of concentrated effort. It’s project management.

To do great work, some people have to tap in. When the work is done, they tap out. To tap in requires 100% of you and no less. A true "tap out" requires you to be at your most relaxed. This seems binary rather than a spectrum and it makes me wonder–if intensity of focus were depicted as a normal distribution curve, would there be disproportionately greater benefits in the 99.7th percentile vs in 64th percentile?

I find the idea of intense attention interesting. When talking about the late, esteemed jazz pianist Bill Evans, jazz drummer Joe La Barbera says:

“Bill spoke of training yourself to focus all your attention when needed. He used the phrase flicking a switch to describe how he initiated the process. And in the two years I worked with him, he never seemed less than 100 percent immersed in the music whenever we played.”

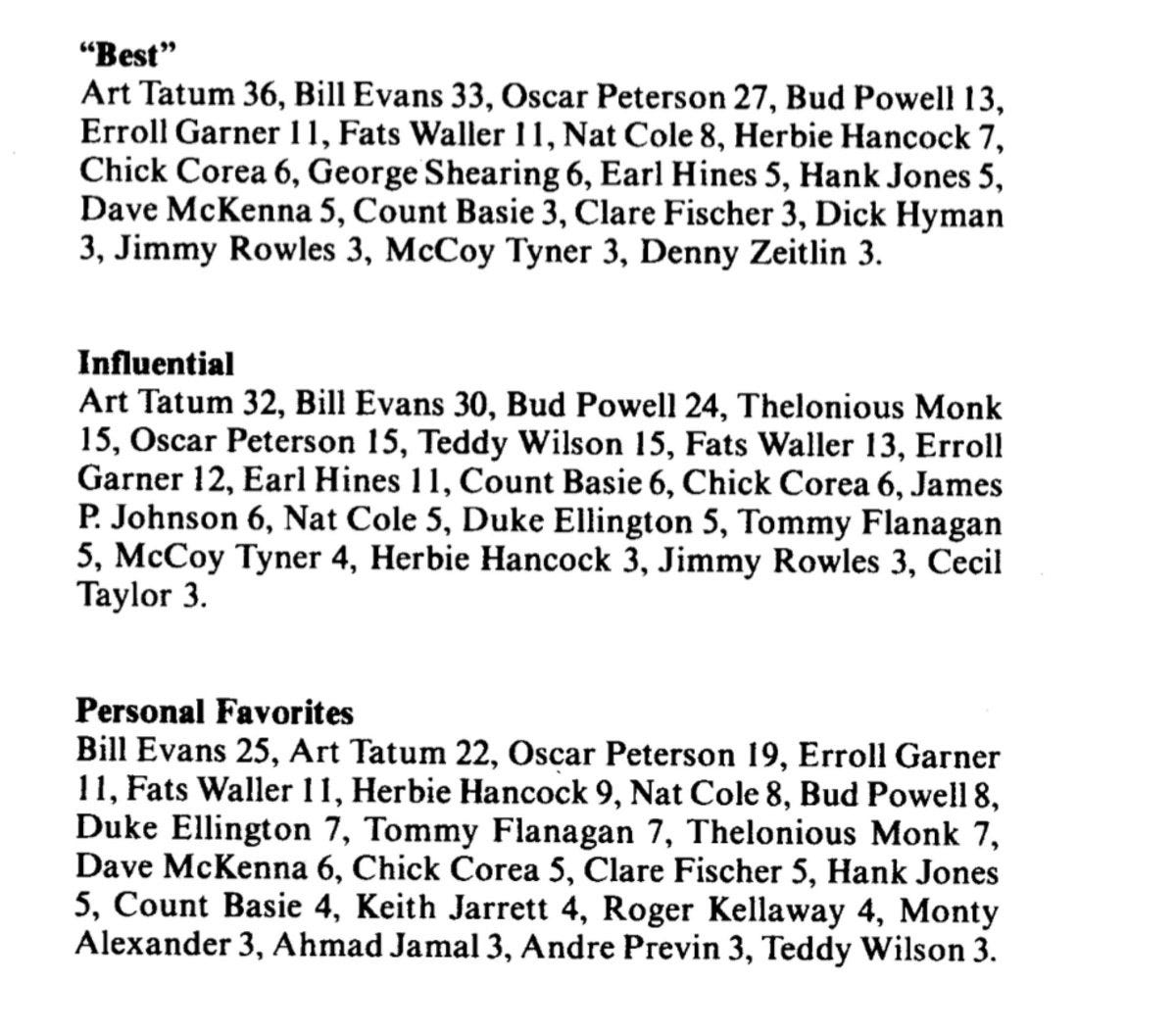

It was this immersion that allowed Evans to put out over 50 albums and earn several Grammy awards. In 1985, a critic ran a survey of jazz musicians (among these were Dave Brubeck, Marian McPartland, Billy Taylor and Dizzy Gillespie) who voted on the best jazz pianist, the most influential, and their personal favorite.

Josh Waitzkin spoke about fighters in a similar fashion. He claims great fighters are fully relaxed when they're not fighting and dial it up in the ring when ready. On a 1-10 scale, we can imagine 1 as fully relaxed and 10 as full intensity. Most people that are in high stress industries seem to be in generally moderate stress (4-6).

"Being at a 10 is like millions of times better than being at a six. It’s just in a different universe. Same as being all-in on a discipline is millions of times more intense than being 98 percent or 99 percent, let alone 'I can take it or leave it.'"

Reading this, I couldn't help but think back to an interview blockbuster filmmaker James Cameron did back in 1999. He likened filmmaking, and the arts in general as a whole-hearted endeavor, not a part-time gig, especially if you're truly committed to it. This full commitment is not reasonable for most people, which is what Cameron refers to as the hard part: "...you have to forswear all other paths because you can't keep a foot in cabinet making, and a foot in directing." He goes further:

"I suspect that many of the difficult and challenging things in the world, whether its research or whatever, certainly the arts, must be all consuming because you're in competition with people who have made that decision, who have committed themselves a hundred percent. You're competing for resources, you know it's just a big coral reef and it's a big food chain and you're competing against people who have made that commitment. If you don't make the same commitment, you're not going to compete."

However, this is not to say it's not possible to be skilled at multiple things. Cameron himself is a polymath–his endeavors in tech, research, design, and cinema make him more complicated than just a director. But those endeavors arose naturally over time as a result of his deep focus on his interests in the environment, sustainability and the deep sea.

It's a bit of a relief to see this binary type of switch some people have when it comes to "difficult" things. I've felt this way with my working modes. When you're chipping away at a diamond wall with bare knuckles, every strike must have your full effort.* Yet, you must give yourself proper time between strikes to recover, rest, and build up strength so you can punch the wall again. And again. And again. Until you strike one day and break through to the other side. In nature, we can liken it to an action potential.

If sufficient electrical stimulus is added to "flip a switch" in a brain cell (neuron), it will suddenly spike its voltage as the electrically charged molecules will flood into it. The cell quickly "resets" after to baseline levels before the spike occurred. The voltage spike never happens if you're under the threshold. The neuron won't "fire."

The prevalence of "exciting things" has made it difficult to commit to any one exciting thing, especially if your loyalty isn't innately driven and unquestionable (think Mr. Beast's unquestionable resolve to make the best YouTube videos or Tom Cruise's commitment to moviemaking). Ava's post on commitment/accountability is worth mentioning here. In it she raises excerpts from "Dedicated" by Pete Davis who in turn brings up Zygmunt Bauman's concept of "liquid modernity."

"We never want to commit to any one identity or place or community, Bauman explains, so we remain like liquid, in a state that can adapt to fit any future shape. And it’s not just us—the world around us remains like liquid, too. We can’t rely on any job or role, idea or cause, group or institution to stick around in the same form for long—and they can’t rely on us to do so, either."

There's little sense of loyalty wherever we look. The foundation is shoddy, and the impermanence of it all is sobering. This is why commitment also commands respect and admiration. Davis continues:

"But when you look at what we have real affection for—whom we admire, what we respect, and what we remember—it’s rarely the institutions and people who come from the Culture of Open Options. It’s the master committers we love. In our own lives, we keep swiping through potential partners, but when there’s a story online about an elderly couple celebrating their seventieth anniversary, we eat it up. In our own lives, we uproot often, but we line up to get into those famous corner pizza joints and legendary diners that have been around for fifty years. We like our tweets and videos short, yet we also listen to three-hour interview podcasts, binge eight-season fantasy shows, and read long-form articles that comprehensively explain how, say, shipping containers or bird migration works."

For many, it's easier to dream and idealize the commitment they see than it is to actually embody it in their lives. However, if you can appreciate the beauty of commitment and immersion, that should signal to yourself that you are capable of it as well.

By the way, if you enjoyed this, you might like reading how Salvador Dali and Thomas Edison used a spoon and metal ball bearings, respectively, to come up with new ideas.

Great one! Something I think about a lot too and recently wrote about to discover where I am focusing my attention and determine if I am spreading myself too thin. Huge Bill Evans fan so always cool to see his thoughts and approaches pop up!